A farm manager ditched the American dream for a wildly successful conservation experiment on a sustainable banana farm in Costa Rica.

Twenty years ago, Álvaro Alvarado Montealto left his hometown in Rivas, Nicaragua, where he had just finished serving as mayor, to chase the American dream. On his way to the United States, he went to visit his relatives in Bribri, the capital city of Talamanca canton in Costa Rica, near the Panamá border. The region is home to Costa Rica’s largest population of indigenous people and some of its most important forests.

Álvaro never made it to the United States. In fact, he never left Bribri.

Finding home on a sustainable banana farm

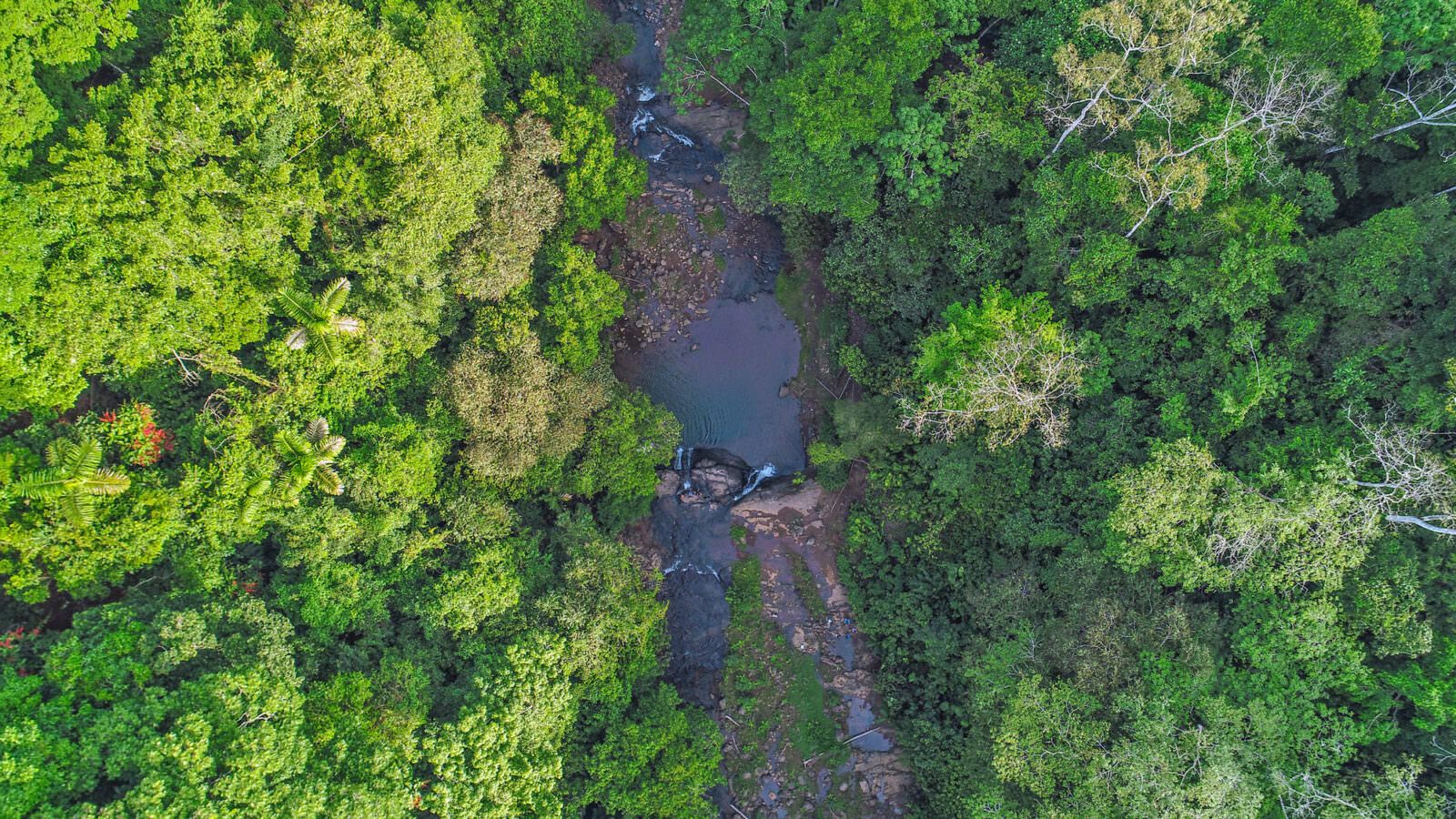

On his uncle’s recommendation, he visited the local banana farm, Platanera Río Sixaola—one of the first two Rainforest Alliance Certified farms in the world—and immediately secured a job as a field worker. “I found a home here,” he said, surveying the verdant expanse nestled between the Gandoca Manzanillo Refuge, which contains the only intact mangrove swamp on the Atlantic coast, and La Amistad International Park, a World Heritage site that protects the largest area of undisturbed highland watersheds and forests in southern Central America.

“I loved the place and loved what the farm was doing,” said Álvaro. He dedicated his life to his new home, working his way up from the field to become the sustainability manager at the 680-acre (275 ha) Platanera Río Sixaola. The farm, founded by German immigrant Volker Ribniger in 1989, has become an internationally renowned model of sustainability.

Healthy forests and vibrant communities are an essential part of the global climate solution. Sign up to learn more about our growing alliance.

Growing bananas—and biodiversity

“We are located in a privileged place, so we are doing everything we can to conserve it for future generations. That means that our main business here isn’t growing bananas; our main business is producing biodiversity, fresh air, and stronger soils,” said Álvaro, 53. With the energy of a teenager and the encyclopedic knowledge of a scientist, he explained the farm’s exhaustive sustainability practices to protect soil health, local waterways, and wildlife.

Water conservation practices

Water conservation practices are fundamental at Platanera Río Sixaola. Early in its sustainability journey, the farm embraced farming techniques that protect water—like manually weeding instead of using harmful herbicides, filling irrigation canals with vegetation that filters out sediment and impurities, and reforesting the banks of the tributaries that run directly into the ocean. Locals in nearby beach town of Manzanillo have noted the positive results 40 miles upstream—they see wildlife returning to coral reefs, and those coral reefs are healthy again.

Soil sonservation practices

Selective manual weeding, rather than toxic herbicide use, also allows ground cover to nourish the soil and help it retain moisture. “Soils love the ground cover. You can find much life in here,” said Álvaro, sinking his hands into the dirt to expose the many insects underneath. “Soils are the main assets we have as farmers, and we can’t afford to destroy them.” The farm even produces its own organic bio-ferments and vermicompost.

A carbon-neutral banana farm

Álvaro’s pride and joy: the 30,000 native trees planted throughout the farm, among the banana plants. Río Sixaola is already 100 percent carbon-neutral, and its staff is now building a huge biological corridor to connect the plantation with its 230-acre (93 ha) secondary forests. In addition, a melina wood forest provides wood for shipping pallets, and forest buffer zones protect local waterways and neighboring forests. The goal is to have a total of 70,000 trees that provide refuge and food to local fauna, including 72 different native and endangered animal species he monitors with hidden cameras.

“Our main business here isn’t growing bananas; our main business is producing biodiversity, fresh air, and stronger soils.”

Álvaro Alvarado, Rainforest Alliance Certified banana farm manager

A successful conservation experiment

Álvaro rattled off a dizzying list of conservation projects he supervises with his infectious enthusiasm: bat “hotels,” the solar energy that powers 100 percent of farm operations, biodegradable bags to cover the banana bunches, a natural pesticide made with chili and garlic to replace chemical pesticides on all but the most badly infected plants, a water-monitoring project for local streams, an environmental education program at the local school, an apiary, and a biotech laboratory to grow beneficial fungi and nitrogen-fixing bacteria for the crops.

“We want to show the world that you can grow bananas while conserving and even restoring forests. And you can also take care of your workers, your community, your people. It costs us a lot of money but buyers and consumers know what they are getting and supporting when buying our bananas,” he said.